“Sister Sara laughed too. 'But dear Sultana, how unfair it is to shut in the harmless women and let loose the men.' 'Why? It is not safe for us to come out of the zenana, as we are naturally weak.' 'Yes, it is not safe so long as there are men about the streets, nor is it so when a wild animal enters a marketplace.’”

― Roquia Sakhawat Hussain, Sultana's Dream

In 2018, I sat in the Academic Building on Rutgers’ College Avenue campus, staring intensely at my screen. It might have been midterms, finals, or the chaotic first week of the semester—it’s all a blur now. What I do remember is locking myself in that impossibly sterile, glass-walled space and diving headfirst into my research. The topic? The implications of dating apps like Bumble and Tinder on human behavior. But I don’t need to dig up my essays from that interpersonal communication course to show you where we are now. Bluntly speaking, we’re fucked—that’s where we are, without raising the alarm too loudly.

As a comms major (sue me) and former party girl, I was well versed in the language and consequences of Tinder on a state school campus—swipes, one-night stands, and pillow talk reduced to fleeting dopamine hits. Yet I couldn’t help but yearn for a meet-cute every single year.

It was easy to yearn, even after every disappointment. The architecture of a college campus teases romance like no other—dome-shaped lecture halls, cafeterias, libraries, and sprawling little patches of lawns. All of it was so sexy to me. It felt like an endless, rotating buffet of potentials: sparks, chance encounters, and moments of prolonged, intimate eye contact.

I’m reminded of why these spaces created this effect on me when read a section called ‘The Circle’ in Design as Art by Bruno Munari. He says, “A circle drawn by hand proved Giotto’s mastery. A circle is always one of the first figures that children draw. When people want to gather closely round to watch something, they automatically form a circle. In this way came the form of the circus and the arena..” The instinct to gather in this way is what creates any sort of connection. It’s primal, ancient, and inherently human.

Besides the unadulterated rise of online dating, poorly designed third spaces continue to hinder our ability to make authentic connections. Think about how many times you’ve stood in lines, content with nothing more than staring at the back of someone’s head. After giving up on that random head, you shift your focus to your phone—scrolling or texting.

I went to see Berlioz at the Brooklyn Paramount earlier this month. At some point during the night, I turned away from the stage and danced with my friend. Everyone looked stunning—winter furs, gloves, funky hats, and shiny leather—but not a single person was facing each other to dance. With all due respect, there was nothing particularly compelling happening on stage, aside from a few beautiful sax solos. So why stare at the stage for two hours? I wanted to shake people’s shoulders and make them turn around to face each other, to look at each other! Why were we all avoiding eye contact as if we were making a sweet escape from several hundred Brooklyn medusas?

Listen, a lot is going on in the lives of romantic fools who are forced to assimilate into the world of modern romance. One such fool is me—thank you for the warm welcome, though I already hate it here, if you couldn’t tell.

Now single for the first time since my college graduation in 2020, I realized nothing fundamentally has changed between the articles I’ve been researching in 2018 and the ones I’m leisurely reading in 2024 about online dating. Though there are some very fun, brilliantly written essays on Substack about our growing frustration with the apps and how our phones are ultimately trying to kill us (totally didn’t see that one coming), we’re all still somehow under the fist of Match Group.

I’ll say it, and I know I’m not alone here: dating apps from 2018 to now have been playing a predatory, claw-on-your-shoulder, stress-inducing, casino-slot-pulling type of game. It’s not normal for an app built on fostering lasting connections to now offer premium subscriptions that let you filter out someone’s height, age, or race.

It’s a game to the makers. But it’s your capacity for understanding romance that’s on the damn line. And all of this—for what? The semi-cautionary guarantee that we (speaking as a woman, but really anyone who can relate) can vet out strangers for our safety while hoping there’s some kind of kismet between an opening line and a voice memo.

I’m not telling you to forgo the apps altogether—what’s the honest fun in that, right?

(Side note: To all the happy, married, to-be-wed, and successfully coupled folks who started on the apps—congrats if you’re one of them! Please, kindly take a seat, this is important for you too.)

What I am going to tell you is this: there’s a million-dollar corporation betting on you failing to find love. But here’s the thing—you’re not failing. You’re just forgetting how to move and think less like a human, and more like a finance bro bot with a ten-minute lunch break before it's off to trade assets—or whatever they do up there.

Part of, I don’t know, behaving more human these days involves taking the flirty little risk of being seen. But let’s not confuse that with SABS. When I first moved to New York, my sister introduced me to this phenomenon called ‘seen-and-be-seen’ (SABS), where people subtly—though not viciously—flaunt themselves in public spaces. I’m not entirely sure how to define it, but here’s an example: on the first hot summer day, Washington Square Park is brimming with people eager to ‘SABS.’

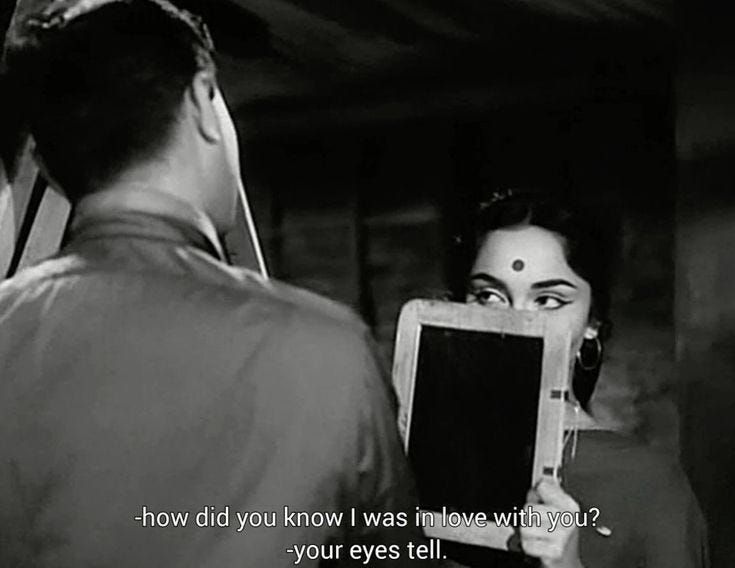

Back in November, after one of our girls' nights out, I was making a case for more eye contact with my friend Samantha. I told her, “I want to make moderate to severe eye contact with men. I’m not ready to date yet, but I do want to practice that.” It’s like exposure therapy—only instead of easing into public speaking or house mice, I’m staring down potential predators disguised as Prince Charming number 24.

The next day, with the birds still chirping, we met down at Wall Street to practice flirting. We called this little adventure #DaddyHunting—a fun, carefree experiment to see what happens when we take up space in spaces where we might meet men. The goal? To work on the art of making moderate to severe eye contact with our desirable matches.

It was harmless, it was silly, and, according to Samantha, the absolute lowest level of effort we could exert as young, sexy women in New York City. Our mission was simple: charm a suit-walker at a café near the NYSE. Why not? We joked about the different kinds of eye contact, startling men on the subway, and even entertained the idea of ‘accidentally’ spilling coffee to grab someone’s attention. It was a morning of honest exaggeration, and I felt a bit lighter knowing that even summoning a meet-cute could have its own dress rehearsal.

But here’s the thing: in New York, it feels like an unwritten rule to avoid eye contact. In a city with so little personal space, the least decent thing you can do is give others agency over their sight and peripherals. Even at events designed for us to ‘see and be seen’ (SABS), there’s surprisingly little effort to actually look at one another. At DJ sets or restaurants, the crowd focuses on a stage or wall art—even when they’re bored out of their minds. Eyes rarely wander to meet another’s gaze.

Eye contact can be quite tricky because when done with intention and desire, it can act as an invitation to something more divine. But more often than not, if we do flirt with our eyes and regret it, we end up like Fleabag in that unforgettable bus scene—awkward, self-aware, and unsure of what to do next.

There’s something vulnerable, almost stigmatizing, about observing someone—or being observed. I think back to Samantha’s words that morning: “What realistically can happen? They look away.”

So, why then does the act of being seen—of truly being perceived— still feel so chilling and uncomfortable?

Social and cultural conditioning rings a bell. As women, we've been raised in a world where men, in many ways, have always been a threat. From the earliest days of human history to the modern era, men have occupied the role of the predator—sometimes literal, sometimes symbolic. But now, as we move through a world far removed from primal dangers, we still carry the weight of that fear, tucked safely beside our neon-colored mace.

How many sparks, how many real connections, could exist between people if women were fully able to be themselves—without the constant hardwiring of caution or hyper-awareness? It makes sense when we're in the woods camping, but why must we anticipate that same feeling on a date? A chance encounter on the train? Why must we?

In Women Who Run with the Wolves, Clarissa Pinkola Estés writes, “The most important thing in the world is to learn to be yourself, and to be with yourself." She speaks of the importance of owning our space, owning our being, without fear, without apology. For women, this has become an act of radical reclamation—a way of reestablishing not just our place in the world, but our power and the ability to truly see and be seen.

She goes on to say, "The wildish woman is the one who does not apologize for her aliveness," reminding us that, in being truly alive, we can be seen as we are—unafraid, unapologetic, and fully human.

I resent how often fear gets in the way of who I could be. But then I remember—we, as women, have always been the keepers of charm, beauty, and art. It’s woven into us, intrinsically. We don’t need permission to be seen, to shine, or to be celebrated—least of all from a screen or an algorithm.

Everything that makes us magnetic, that sets us apart, is already inside. What would our lives look like if we could embrace it without hesitation? Without the constant shadow of doubt, or the endless questioning of our safety, or whether we’re “doing it right”?

If we were truly free—unburdened by fear or defense mechanisms—we wouldn’t need rose-tinted glasses to see the world’s beauty. Because, in that freedom, the world itself would already be drenched in that color.

But we’re not free…yet! So keep a light pulse on your Hinge profile my angels, and be sure to make prolonged eye contact with at least three strangers today. Who knows—you might find the look of love along the way.

Finally got around to reading this- so well written and thought provoking ❤️

This is so profound. As a girl who battles with undiagnosed social anxiety and a crippling inability to make eye contact. This article filled me with immense longing.