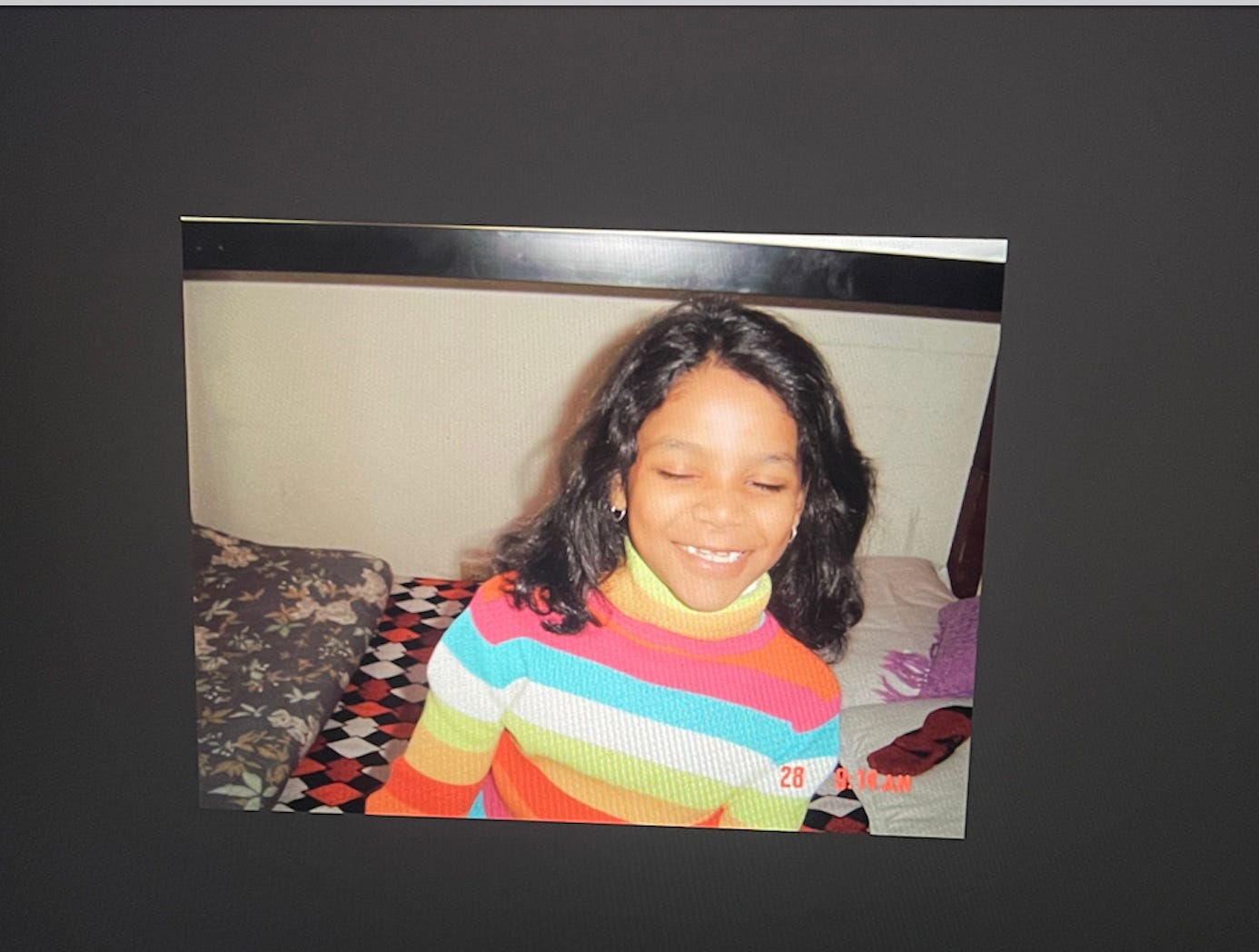

A few years ago, I wrote in my journal a question: What would it feel like to be led by curiosity instead of fear? Though this was an effortless, nearly invisible task as children, in the digital age of being everything, everywhere, all at once, I’m left living with, in, and out of fear more than usual. I remember a time—up until I was twenty-one—when I was living fearlessly. I moved through life with grit, tenacity, and a healthy dose of oblivion to the kind of self-awareness that suffocates you with decision paralysis.

I reminisce often, sometimes without even thinking, in my journal about that version of me. I can trace her charm with my pen, while also outlining her anxieties, insecurities, and dictations. At the same time, she feels far removed—like a stranger who brushed against my shoulder once in passing on the street. She was light. She was wide-eyed and hopeful. She turned to the world with a lens left unclear but she preferred it that way. Though snarky and cynical at her core, she always knew when to let that side of herself slip through.

They say, do not dwell in the past, for it only brings suffering—at least, that’s the godlike, codified wisdom I get from relatives on WhatsApp every so often, paired with an image of a sunset or a lotus flower. But I’m not raising my hand and saying I dwell in the past. No, it’s more like I’m gripped by it. White-knuckled, sweat-soaked, pathetically static—stuck in one version of nostalgia that may never hold any objective truth. And yet, here I am wondering if it’s the past itself or the comfort of believing it was real that I’m drawn to.

I fall into this kind of existential dread when the occasion demands it (half-a-lie): writer’s block, rejection from 300 job applications, a blank manuscript, motivation crumbling, weeks of isolation, a breakup, or watching more twenty-four-year-old women appear on talk shows for their book deals.

My therapist always reminded me I’m too hard on myself. I never told her I didn’t know how to exist any other way. If I can’t succeed in my way, with the visions I had in mind, then what’s the point? Why bother trying? People will tell you it’s about the process. I’ve written enough think pieces on finding joy in the process for me to lie to you and say that the process is anything but painful. It’s soul-sucking, and it feels like an empty dimension where you’re forced to confront two things at the same time: some embodiment of your potential and plain old you, right now. I’m sorry, but only a masochist would enjoy that experience.

Then there was an interview I came across that changed everything for me. It was by Maya Kotomori on Document, where Bill T. Jones and Hank Willis Thomas discussed creative freedom and the intersection of art and humanity. At one point, Hank mentions a book called Finite and Infinite Games by theologian James P. Carse.

He says, “In this book, there are two types of games. Finite games come to an end when there’s a winner and a loser. But the goal of an infinite game is to remain in a state of play. And therefore, the rules always have to change. When I look at our society, I think about some of the people who are most reviled. They often are infinite game players, because they wind up breaking the rules so they can keep playing.”

As someone who looked to rules and guidelines to help navigate my life the way a Baptist church looks to the Bible for moral direction, I found this new perspective unsettling in the best possible way. It made me realize I had played this 'infinite game' before—as a child. Most of the activities we remember as children were, one, inherently participatory, and two, carried low stakes when it came to winning or losing—because we weren’t playing to prove anything.

Even when we played to prove something, it was often for an adult whose attention we craved, holding their approval over our heads. Like when I played tennis alone against the wall—always trying to win, even when no one was watching. But the wall was always watching.

Aside from these games came universal gestures rooted in promises, imagination, and wishes.

Coin tosses. Cloud guesses. Double dares. Eyelash wishes. Finger bangs. Finger crosses. Magic tricks. Pinky promises. Paper boats. Paper planes. Staring contests. Shooting stars. Secret notes. Shadow puppets.

As adults, we encourage these things—we marvel at them and hold them up as memories of innocence and purity. Yet we forget the freedom they represent the moment we decide we are worthy of adulthood. I believe there’s an unconditional responsibility to protect the very essence of childhood—not just through education or paternal care, but by creating a world where adults can step into a childlike state again. Without judgment. With grace.

I read J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye as a child. Now, as a soon-to-be twenty-seven-year-old woman, I understand Holden when he talked about catching kids from falling off a cliff:

"I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going, I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all."

Instead of creating spaces where children are taught to become "better adults," I want to imagine a world where they’re allowed to simply grow up. A world where growing up doesn’t mean shedding wonder for fear or sacrificing curiosity for conformity.

Becoming an adult comes with trouble and ill-willed guidance from those who have worn fear like a mask for years. I refuse to wear that mask to operate my day-to-day—the mask that says, This is me, this is my reality, I am an adult, and I am better off as one.

I don’t ever want to be that kind of adult. I want to grow up and keep growing up—until the wrinkles fold softly with every new pound of flesh I accumulate. Until every hyperpigmented mark on my skin fades into a lighter, duller shade of brown.

I envy that kind of freedom—the way children created rules only to break them, treating play and even boredom as boundless, with no pressure to win or fear of wasting time. Before we even understood the word "freedom," we all lived it once before—curious, unbothered, and unshackled. As children, we were the closest thing to magic itself, instinctively knowing we were all we needed to make something happen.

It’s probably why, when the weight of adulting and making a living starts to sting, I find myself leaning into the things I loved as a child: crafting the perfect sweet-and-salty snack combo, wandering through the children’s book section at libraries and bookstores, hopping on a carousel whenever I see one, binging my favorite animes, searching for the moon on my walk home, rewatching early 2000s South Indian films, listening to Studio Ghibli soundtracks, writing in journals and tucking them away in a locked cabinet, collecting pens and bookmarks, eating cereal at midnight—the list goes on.

I find comfort in the younger version of me that once existed—the one who played with life, even challenged it. She was bold. She was emotional. She was distressed. She was confident. She was relentless. She didn’t ask for permission to exist fully, to feel deeply, or to carve out her meaning in her ambitious pursuits. She moved through the world with a kind of unshakable energy, not burdened by what might come next. And I miss her terribly.

Though nostalgia is a great place to visit, it’s not somewhere to settle down. Whenever I overstay my welcome, I feel it in my heart. It holds this emptiness like a damned vase devoid of any flowers. It’s the same feeling I get when I confront my potential during the process of writing— that mixture of possibility and pressure.

But then I selfishly reach for the version of me who knew how to play without hesitation, shaking her shoulders and asking how I can be her again — not all the time, but when I need her confidence, her ease. I ask her if we can play together this time, over and over, until we’re both bored of the ending. Until we find something new to get lost in.

resonated so deeply, thank you for putting it so eloquently into words🤍

this spoke to me so deeply and viscerally. a stunning piece 🩷